Still hoping for the world we want

It was two in the morning when a chartered bus carrying 30 idealistic teenagers drove up to a hangar at New York’s Kennedy airport where a propeller-driven Iceland Airlines plane bound for Brussels was waiting just a short walk across the tarmac.

Bathed in the glow of the airport lights, the plane looked like a shiny toy made real by some trick of the same fate that had brought me into this group bound for eight weeks in Europe. We were the 1965 summer delegates to the “New York Herald Tribune” World Youth Forum, and we would be spending the two months before we started college touring Europe and learning about the history, economy, government, and culture of the countries we visited.

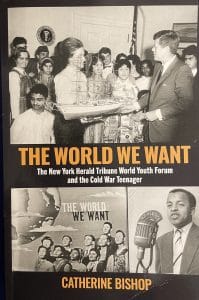

All of this comes back to me now in vivid detail as I read my journal from those long-ago times prompted by the October 2024 launch of Australian historian Catherine Bishop’s book, “The World We Want: The New York Herald Tribune World Youth Forum and the Cold War Teenager.”

The book is a fascinating read for anyone interested in the intersection of U.S. foreign policy, newspaper journalism, and the psychology of teenagers growing up during the Cold War. Like a good therapist, the author provided me with a context for what I was doing all those years ago when I joined 29 of my peers on the adventure of our young lives.

We lived in hotels, youth hostels, with host families, and, for one memorable weekend, on the grounds of a large psychiatric hospital in Denmark. Our teachers were university professors, government officials, businessmen, host family members, peers, and, on one occasion, the president of West Germany who received us for tea at his residence in Bonn.

We traveled by plane, train, bus, hydrofoil, and ferry, witnessing the renaissance of Europe after the devastation of World War II 20 years earlier. Two decades were not enough to revive East Germany liberated by the Russians and still littered with the bombed out remains of public buildings and private homes. From the windows of our train, we saw long lines of people waiting to enter small isolated food stores. Scenes of desolation passed before our curious eyes while a voice piped into our compartments touting the prosperity of the German Democratic Republic.

In East Berlin, we were transferred to a local train where East German police, with guns poised, searched us before we pulled out of the station under a scaffold where another policeman aimed his rifle at the top of the train. This was to avoid a repeat of a recent successful escape to the West through the infamous Berlin wall. Later that week, we would return to East Berlin as a group in a guided tour, and I would go back with a friend to explore the city on our own, sweating out a search at the border that luckily did not find the East German marks I was bringing home as a forbidden souvenir.

This all happened in the summer of 1965 in an offshoot of the Tribune’s World Youth Forum that brought 807 students to the United States from Europe, Asia, South America, and Africa, about 30 per year, from 1947 through 1972. The summer program, which ran from 1964 to 1972, was a Forum in reverse, sending Americans to Europe in a much less ambitious enterprise with the same goal of fostering mutual understanding. The hope was that friendship and empathy born of first-hand knowledge of peers from other countries would lessen the chances of another war.

With this goal in mind, the New York Herald Tribune invited selected countries to send first one and later two delegates each year to New York from January through March where they would live with three American families and attend three different high schools.

Delegates would take turns participating in weekly televised panels where they would discuss world issues and answer questions from the moderator about their lives at home and their impressions of America and the lives of their American peers. The show became popular and some delegates were surprised to be recognized on the street.

There were group excursions to museums and other attractions, meetings with dignitaries and, for some lucky delegates, tea with Eleanor Roosevelt and receptions at the White House with Presidents Eisenhower and Kennedy.

Delegates were chosen carefully by the ministries of education of their home countries. The process began with an essay on some variant of “the world we want.” Malaysia, for example, stressed “unity in diversity” because of the multicultural patchwork of Malaysian society. An interview followed, usually with the Minister of Education and sometimes also with an official from the United States Embassy. In her book, Catherine Bishop refers to the winners of these competitions as “the chosen ones.”

The United States delegate was selected through a series of discussion panels where the student judged to have given the best performance would advance to the next round, beginning in local high schools and moving on to the CBS television studios in New York. The winner became the United States delegate for the following winter and together with 29 runners up toured Europe in the preceding summer.

As a runner up, I was reluctant to give up my last summer with my friends before starting college, but the encouragement of my family, my curiosity about the bigger world, and the return of common sense put me wide-eyed on the plane to Brussels. It was one of the best decisions I ever made.

In the years since my retirement, I became curious about what happened to the Forum and, through the magic of Google, learned that while the program ended in 1972, there was an active alumni association. Reunions had been happening all over the world, often of people who had never met but had the Forum experience in common. A publication, The Delegate, carried news of what the alumni were up to and often asked readers for their opinions on various topics.

I joined the club and responded to a question about aging with the observation that the Forum had opened my eyes to countries, cultures, and people that I would otherwise never have met. This exposure taught me or reinforced what I somehow already knew that we are all more alike than different. It was the same lesson that my career in psychology would repeat over and over again in the inner city, wealthy suburbs, and locked wards of state hospitals.

In the years that followed, I have been privileged to participate on a Forum committee that plans and presents Zoom discussions, not so much on the world we want but nowadays on the world we have. The difference between these worlds spans a wide chasm between peace and war, opportunity and inequality, prosperity and poverty. Perhaps it has always been so, and perhaps the chasm has narrowed. Can we really say of any passing generation that it is satisfied with the world it is handing on to the next?

We can say we tried. We did our best. In a masterful summary of the impact of this 25-year experiment in international cooperation, Catherine Bishop reports that about 10 percent of the 807 Forum delegates became global leaders as presidents, ministers, diplomats, and others in high positions in international business and academic circles. There is scant evidence of former delegates interacting with each other on the global stage to change the course of history, but we can never know the subtle effects of the friendships we made and attitudes we formed in our early years. We can hope that the Forum experience gave us a global perspective and an appreciation of our interconnectedness on this small planet that we call home. We can hope this made a difference and that we can continue to find ways to put these values into practice in all that we do.

When she was just 17, Dorothy Chen-Courtin, the Malaysian delegate in 1962, ended her winning essay with these words, “Only if man meets man on the basis of their intrinsic humanity can they really get to know each other’s true worth and thus evolve a means for unity and cooperation.”

These words are just as true today as they were then. The challenge is just as real, the stakes higher than ever.

Note: For more information about “The World We Want,” please visit https://scholarly.info/book/the-world-we-want-the-new-york-tribune-world-youth-forum-and-the-cold-war-teenager/