My life in the library

When I retired from my hospital position nearly seven years ago, I moved my office to the public library. It was an easy move – no furniture to rearrange at home or haul across town to a new building, no rent to pay and a short commute for the pleasure of getting out of the house whenever I want to vary my routine.

I’m here now, still masked against COVID and tapping the keys of my MacBook, the sole occupant of a table for four in the periodical room, writing in the late afternoon light pouring in from a wall sized window that looks out onto the Italianate city hall across the street.

This is my latest library, my home base for the past 40 years, and as I sit here reflecting on the passage of time, I appreciate more than ever the role libraries have played in my life and the way they continue to serve the public good.

The Internet, which I can access from my own MacBook or from a bank of laptops on the second floor, tells me that the first systematically organized library in the ancient Middle East was established in the seventh century BCE by Assyrian ruler Ashurbanipal in Nineveh in contemporary Iraq. It contained approximately 30,000 cuneiform tablets with text inscribed in clay.

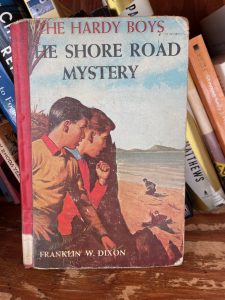

The Great Library at Alexandria in Egypt founded in the third century BCE is believed to have held as many as 700,000 documents from the ancient world. My first library in 1950s Carteret, New Jersey had all 38 of the original Hardy Boys volumes, and that’s what mattered most to a kid tasting the sweet joys of reading for the first time.

The Carteret library was a clapboard house at the intersection of two main streets. The front of the building with its peaked roof faced Carteret Avenue, a broad thoroughfare with a median strip planted with spindly trees that ran from the factories at its eastern end to the toney Shore Crest estates in the west. It didn’t matter that the flat land of the estates had neither shores nor crests. The cachet was in the name. Pershing Avenue along the north-south axis was the town’s only bus route, where buses ran from Perth Amboy in the south to Newark and Manhattan in the north.

A short walk from my grammar school or a longer one from home brought me to the front door of the library and, just inside, the circulation desk, a few tables and chairs, and rows of steel shelves groaning with what I could only imagine were more books than anyone could ever read in a lifetime.

I came for the Hardy Boys, an only child who wished he had brothers like Frank and Joe Hardy who went around all day helping their detective father solve crimes. I didn’t have a brother, but I had my best friend Bobby, an all-around scholar athlete in the making, the kind of kid you had to admire, the kind of kid who inspired you to be your best self in anything you attempted.

We competed in everything including how quickly we could read all of the Hardy Boys books. I don’t recall who won or if either of us ever managed to read all 38, but I am forever grateful to Bobby for his example in this and so many other things in life.

Later, in my high school years, I came for the information I needed to write term papers. Before the Internet, before Google, before Wikipedia, there was the Encyclopedia Britannica, which sat with its brothers The World Book and Colliers on the shelves in the reference area. Some households had their own volumes of these prestigious works, sold door-to-door by encyclopedia salesmen, zealous as preachers and persuasive as carnival hawkers. Think of the advantage your children will have in school, in life, if they had all the information they would ever need right here at home, in your own handsome 24-volume set of the Encyclopedia Britannica. Some families took the bait and their advantaged kids wrote their terms papers at home. The rest of us went to the library.

We went to the library and hefted the book we wanted onto the table, turned to the entry we were looking for and learned how to put what we read into our own words.

The library was also the home of Masterplots, a thick volume containing summaries of the world’s great literature including the books on the required reading lists of our high school English classes. It was the kind of book you might expect a group of four or five teens, behind in their reading with a book report due in the morning, to huddle over, each one peering over the shoulder of the lucky kid who got to it first, just to get the gist of the story. If you were to ask me whether I ever saw a scene like this playing out in the library or whether I was ever part of such a scene, I would have to take the fifth.

One library leads to another, and my first brought me to this table in the periodical room where I sit now reflecting on the journey. The college reading room where a black- robed monk blessed us from his portrait on the wall, cinder block cubbies in the stacks in graduate school, vaulted ceilings arching over carved wood-paneled walls in my internship year, and the concrete and glass medical library where I wrote my dissertation – all are part of my life in the library where thought fuels action, the past informs the present, and the future lives somewhere in that gaggle of kids just coming in through the door.