Study finds lack of data a barrier to systems-level research on patient safety

Morgan Shields admits she was naive in the summer of 2017 when she first submitted an online public records request for all substantiated complaints against inpatient psychiatric facilities in Massachusetts.

Morgan Shields admits she was naive in the summer of 2017 when she first submitted an online public records request for all substantiated complaints against inpatient psychiatric facilities in Massachusetts.

The paralegal from the Massachusetts Department of Mental Health (DMH) who called her told her it would cost more than $100,000 to provide the records.

“I thought what he was saying was it would cost the state that much money to redact all of the information, just go through all the files,” recalled Shields, a Ph.D. candidate and National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism fellow at the Institute for Behavioral Health at Brandeis University’s Heller School for Social Policy and Management.

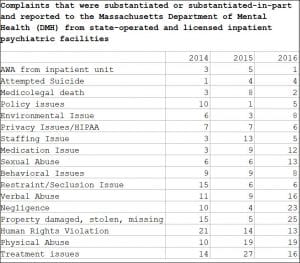

The paralegal convinced Shields to pare down her request to only the past few years so the records could be provided at no cost to her. Three weeks later, she received a file from the DMH on the different types of complaints that were partly or fully substantiated from state-operated and licensed inpatient facilities from 2014 through 2016.

The data helped form the basis of her research study published late last year in Health Affairs highlighting how inpatient psychiatric care has been neglected despite concentrated efforts to measure patient safety in other settings. While government websites give star ratings to general hospitals and nursing homes, consumers have little information to go on when it comes to learning about how well free-standing psychiatric care facilities perform, Shields said.

The data she collected showed there were eight deaths in Massachusetts inpatient psychiatric facilities in 2015, three in 2014 and two in 2016. Other complaints included:

- 19 complaints of physical abuse in both 2015 and 2016, up from 10 in 2014.

- 13 complaints of sexual abuse in 2016, up from six each in the years 2014 and 2015.

- Four complaints of attempted suicides in both 2015 and 2016, up from one in 2014

- 21 human rights violations in 2014, which decreased to 14 in 2015 and 13 in 2016

- “Treatment issues” totaling 27 in 2015, 16 in 2016 and 14 in 2014.

- Complaints about a “staffing issue” jumped from three in 2014 to 13 in 2015, then five in 2016.

“I was shocked to see the number of complaints and the number that were actually substantiated because that’s a very low, low estimate of the true events that are happening,” Shields said.

“To substantiate some of these claims takes a lot of resources and is hard. It doesn’t mean it didn’t happen, it’s hard to substantiate some of these incidents.”

Shields said she was also surprised by the lack of a robust internal monitoring system that could distinguish who reported the complaints. Not being able to track if the complaint originated with a patient or staff member or other observer complicates efforts to try to understand the root causes of problems and how the reporting system can be improved.

Her research has not gone unnoticed.

“The study clearly documents the lack of federal and state government investment in safety monitoring and quality improvement in inpatient psychiatry,” said Tami Mark, Ph.D., MBA, a health economist and expert on behavioral health care financing and delivery.

Mark who is senior director of behavioral health financing and quality measurement at RTI International, a non-profit research institute based in Research Triangle Park, North Carolina, led a study published in Health Affairs in January 2018 documenting why consumer report cards are needed in addiction treatment settings.

The study called for private and public sector investment and collaboration to develop public reporting systems that will improve accountability and patient outcomes.

DMH says it will implement a new safety management system for complaint and incident reports, by July 1, 2019 at its licensed hospitals. The new system will improve data collection and allow the department to identify trends that impact the patient experience and improve care, according to a statement provided to New England Psychologist.

“The Massachusetts Department of Mental Health (DMH) is committed to creating a culture of safety in our inpatient hospitals,” the statement reads.

DMH said it administers ongoing inpatient satisfaction surveys and distributes the survey results to hospitals on a quarterly basis and meets to discuss the findings and opportunities for quality improvement based on results.

In addition, an annual community consumer satisfaction survey seeks to understand the experience of adults and young persons served by the department and provide information to develop recommendations to improve the quality of community programs.

There were 107 cases of alleged abuse, neglect, and rights violations closed by an advocate or attorney in Massachusetts in fiscal year 2016, according to a 2018 Governmental Accountability Office review of the state’s participation in the Protection and Advocacy for Individuals with Mental Illness (PAIMI) Program administered by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Program.

Of those 107 cases, 86% were resolved in the client’s favor.

Massachusetts, one of eight states evaluated in the GAO report, had more cases closed in the client’s favor than the average of 74.1%.

A closed case means that an attorney or advocate determined that “the client either had no need of further services or that the program had no other services available to address the problem(s).”

Closed in the client’s favor could indicate the client “was satisfied with the result of the program’s work or the violation in the stated case problem area was remedied.”

Remaining cases were reported as withdrawn by the client, closed because of lack of merit, or not resolved in the client’s favor.

Shields emphasized that the substantiated complaints data she collected is not the same as the data PAIMI collects.