The joy of reading

“Some books are to be tasted, others to be swallowed, and some few to be chewed and digested…” – Francis Bacon

Tasted, swallowed, and digested – I’ve done them all. Though I can’t remember when or how I learned to read, I imagine it happened in the usual way with a first-grade primer and a story about a dog named Spot.

Perhaps my mother sat down with me when I brought the book home from school and helped me sound out the words. The grocery store across the street from our house had a carousel stocked with Little Golden Books, those slim, gold-edged books of all the classic fairy tales that I learned one by one, first by listening and then by trying to decipher the words and the sentences on my own.

By the time I was in second grade and because I attended a Catholic grammar school, I could read the Baltimore Catechism, a question-and-answer guide to all the theology a seven-year-old would ever need to know.

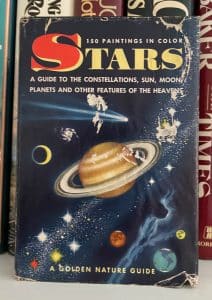

I could read and recite the answers to questions about who made me and why, and what I had to do in this life to be happy with God in the next. A few years after that, I noticed in our grocery store carousel a colorful book with the simple title, “Stars,” and asked my mother to buy it. She was always an easy mark for books, just as long as I didn’t grow up to be “bookish,” by which I think she meant a person with more book knowledge than common sense.

“Stars” drew my attention to the night sky and my imagination to the faraway worlds of the dark side of the moon, the canals on Mars and the giant outer planets of the solar system. What we could see of that sky was limited by the streetlights and air pollution of the small factory town where I lived, but a friend with a telescope taught me how to search out small circles of sky where clarity and silence prevailed.

In one of those circles, Saturn with its perfect rings floated across my field of view as the Earth where I stood carried me under the planet’s shining orb.

Soon I was reading everything I could find about astronomy. Field guides to the heavens showed me where to find Venus and Mars, the brightest stars, the constellations and rarer sights like double stars, clusters, and wisps of cosmic dust and gas where fainter stars were being born or dying.

I subscribed to Sky & Telescope magazine where I marveled at the photos of the night sky, used its star charts to find the observing highlights of the month and labored through articles on the physics that held the universe together.

I found my sources in our little town library where the shelves also beckoned with all 38 volumes of the Hardy Boys novels that told the story of three brothers who helped their private-eye father solve crimes.

A science fiction novel scared me with its description of a machine capable of reading people’s thoughts, some of which I preferred to keep to myself even as a boy of 11 or 12. Another book, “Men in Sandals,” gave me a glimpse of the life of a monk, which like many of my friends, I once considered.

At home, there were copies of Readers Digest, Robert Louis Stevenson’s “Kidnapped,” and a thick so-called wonder book of everything that explained how things were made.

I remember turning first to the chapter on the construction of the Lincoln tunnel under the Hudson River to learn how such a seemingly impossible thing could be done. The question niggled me each time I rode the bus from my New Jersey home to Manhattan, scanning the tile walls of the tunnel for the first signs of dripping water. For a while, I asked for and got a copy of the “World Almanac” every Christmas where I collected what would later be called trivia – lists of the longest rivers, biggest cities, and tallest buildings the world over.

High school brought the classics of English literature, and Latin gave me Julius Caesar, Virgil, and Cicero. College added more Latin and British classics and introduced me to poetry and the works of James Joyce.

Graduate school was a blur of textbooks, journal articles, and a few memorable gems like Alexander Luria’s “The Mind of a Mnemonist,” Jerome Frank’s “Persuasion and Healing” and, on the recommendation of a classmate, the lyrical writing of naturalist, Loren Eisley.

In the years that followed, I have tasted, swallowed, and digested more books than I can remember but not nearly as many as I would have liked to experience. I say experience rather than read because I have come to believe that a good book brings the reader into an experiential space of sight, sound, taste, smell, and touch. It appeals to all the senses and uses them to transport readers into a story where they meet characters whose journeys they share.

The journeys of biographies and histories are factual, but the best of these works show us how the protagonists live the facts of their lives and times, how they process the information that structures the challenges they face, and how they feel about the decisions and courses of action they follow.

Novels enlist the imagination to give the reader a wider variety of characters, settings, and situations than real life can provide and, in so doing, strengthen our capacity for empathy and creativity.

And when it comes to economy of expression and the pure beauty of words artfully arranged, you can’t beat a good poem or a piece of lyrical prose. Savoring the joys of my own reading over the years, I am grateful for those field guides to the night sky and yearly almanacs that first showed me where I was anchored, for those books that still tell me everything I need to know about anything I want to learn, for the chronicles of those who have gone before me, for stories that help me to imagine how things might be different, and for the sound of well-chosen words that linger long after the book is closed.

August 2nd, 2023 at 3:35 pm Martha posted:

Martha posted:

Dear Dr. Alan

Thanks you for sharing your reflections on reading over the lifespan! And to end up with gratitude to the solar system field guides and the artfully arranged words of poetry. Yes! It was a pleasure to read along.

Dr. Martha in Maine